That Gorebridge would be chosen as the site for the first industrial scale gunpowder works in Scotland may seem a bit odd in the modern day. However, in 1794, three Englishmen would eventually settle in Gorebridge and begin the process of consolidating the largest gunpowder manufactory in the country. This article will chart the reasons behind choosing Gorebridge as the eventual area for the enterprise, its development, and its demise as the industrial revolution took hold of the nation.

Prior to relocating to Gorebridge, in 1791, both John Hunter and William Hitchener had tried to gain a licence for manufacturing gunpowder in their native Surrey. After petitioning the local courts, it was deemed that neither Hunter nor Hitchener had the necessary skill set to be capable of safely maintaining such a dangerous site. Hunter, a millwright, and Hitchener, a farmer, were neither regarded as being experienced enough in the trade, or likely to become so. Furthermore, the magistrates ruled that the proposed location itself was a danger to the public good, factors such as its proximity to local roads being decisive. After rejection, both had informed the court that they would seek an appeal of the official decision, but this does not seem to have been forthcoming.

The next record we have of the two is the successful application to magistrates in Midlothian. By this time, 1794, they had acquired an agreement with another keen partner, John Merrick. The agreement with Merrick was crucial, as he would be the crucial experienced hand which would run the enterprise. With little difficulty a license was granted, and after leasing the ground (part of which was the site of an earlier corn mill) from both Vogrie and Arniston estates, construction began.

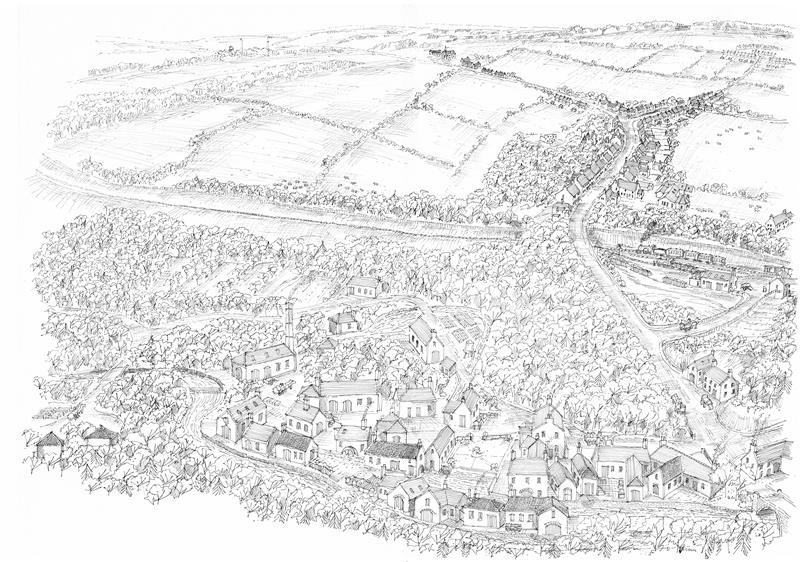

Gorebridge as a location in the late 18th century would have appealed greatly to any prospective manufacturers, especially one so dangerous as gunpowder making. Firstly, as an underdeveloped land, relatively secluded and isolated, there was little danger of any impact on a pre-existing community.

The nature of the valley was also of great benefit to the endeavour, the steep valleys could act as a natural barrier, sheltering both the outside and inside from the potential hazards of explosion. Naturally this also had the added benefit of the power of the Gore as it surged through the valley, ensuring that hydrology could be used to power the mills on site.

Getting materials needed for the manufacture into the site, and getting gunpowder out of the site, was also a vital ingredient for the choosing of Gorebridge. Local trees could be planted as part of the lease agreement with the landowners, while in the meantime, ash and poplar trees could be used from Crichton Moss for charcoal. Similarly, the proximity with Edinburgh meant that the other raw materials (sulphur and saltpetre) could easily be imported from abroad via Leith docks, and onto the Waverley Rail line. Just as easily, manufactured gunpowder could travel in the opposite direction. Local demand for gunpowder in mining, quarrying and railway construction meant that, without exporting abroad, there was widespread local demand – unimpeded by any Scottish competitors at that time.

The Development of the Site

From the outset, it was apparent that John Merrick was responsible for the day to day running of the enterprise, however short his tenure would end up being. Supervising both the building of the mills and the general management of the site, Merrick would be entitled to either £100 per annum or 1/8 of the sites profits – whichever was greater. Hunter and Hitchener would be responsible, however, for covering the entirety of the running costs.

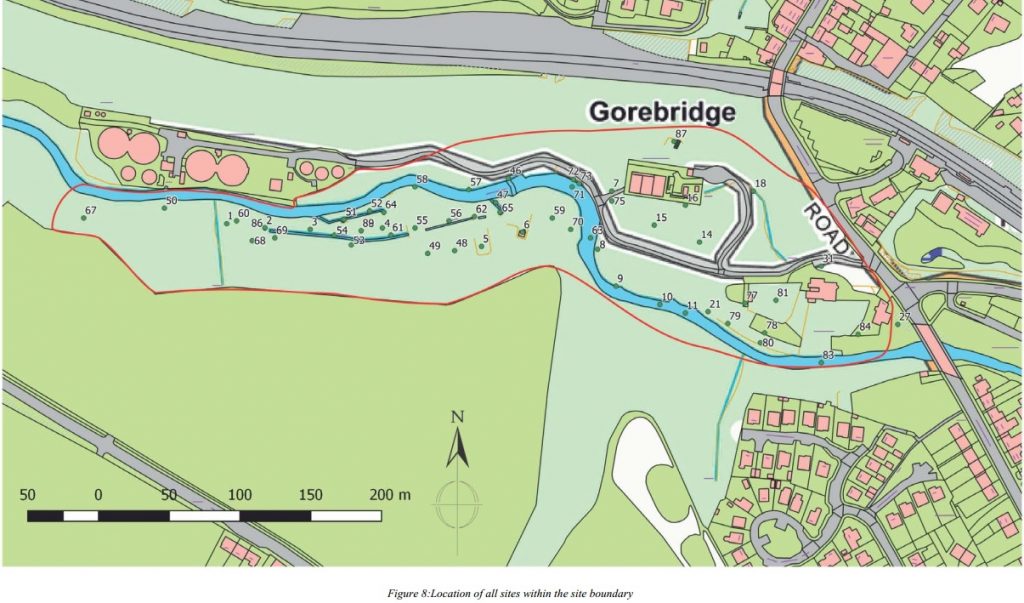

Merrick set about fulfilling his obligations extensively. His contract stipulated he was required to employ the whole of his time, skill and attention in superintending the erection of houses, mill buildings and machinery [and then] constantly reside in and about superintending, overseeing and managing the said works machinery and manufactory. Throughout the major engineering process undertaken, no less than four dams were built up the Gore water to divert the flow, including a complex system of lades which shepherded the water to ten water wheels, one of which was 20ft in diameter.

This complex water system would channel water to the various buildings which required water power. In total, 30 buildings had to be constructed to house the various manufacturing processes as well as to store the required materials and finished product. Theses buildings, especially the more dangerous facilities, were built far apart and in secluded spots surrounded by earthen and man made banking’s – leading the site to stretch over ¾ of a mile.

While the works were extended some time before 1814, this would have been supervised under new general management. A legal dispute was raised in the early 19th century between John Merrick and Hunter and Hitchener over how Merrick was being paid. This looked set to go through the courts before an explosion on site sadly ended the life John Hunter, while on site at Stobsmill House. This seems to have been the final straw for Merrick, who quickly left and set up the Roslin Gunpowder Works at Roslin Glen, in direct contravention of his previous contract.

Until this point, safety precautions were hardly existent on site. Metal tools were regularly used throughout the various stages of manufacture, leading to the types of explosion which took the life of John Hunter. It appears to have been such concerns, as well as contractual disputes, that Merrick’s time came to an end at the site in 1803.

The lease for the site ended in 1844, by this time further changes had taken place on site to accommodate the coming of the railways to the village. While the lease had ended, the site continued to operate with these changes until closure in 1865.

The Demise of the Site

The closure of the site doesn’t mark the end of its history and relationship with the village. An advert in the Scotsman in 1865 appeared to be advertising the site for its current use. However, the progression of the industrial revolution (a revolution which the gunpowder works helped develop) rendered the site unprofitable.

By the time of its closure, the site only employed a third of the employees it did at its peak, and the layout of the site made it unsuitable for the new hydro-electric power which was beginning to power mill enterprises.

As a result, no offers for the standing structures were forthcoming and the site passed back into the hands of its respective owners before Robert Dundas of Arniston House bought the land to the north of the river from Vogrie Estate. After doing so, he landscaped and demolished elements of the site to create a driveway to his mansion – connecting his house with station road. In the process, he planted additional trees in the area, leading to the more densely wooded area we have today. Leaving ruins and a wooded driveway designed to create a ‘romantic atmosphere’.

Ordnance survey maps from 1895 and 1908 show little change in the layout of the site between this time and 1946 aerial photography shows that by this time it had become densely wooded with both coniferous and deciduous trees.

Since then the site has continued to fall into disrepair.