Number 26 Main Street, better known as ‘Whitie’s Shop,’ hints at a story which has passed into the shared memory of the local community. The premise, currently housing a solicitor’s office, offers what is perhaps the most intriguing insight into the construction and functioning of an early commercial enterprise on the Main Street. This article will offer a brief overview of the consturction, development and history of the former trade shop.

James Whitie, descended from a long line of shoemakers originally from Peebles, set up his shoemkaing store in direct competition to three other shoemakers in the town run my messrs Scott, Reid and Bain. Originally having set up shop on the East side of the street, his ambition and hard work led to the establishment of the surviving premise. Built in 1880, the west side of Gorebridge Main Street was not completely built upon, an empty site which Whitie took advantage of as he leased some of the land and had plans drawn up for a substantial building. These plans included a shop with an office and back room, a work shop and cellars in the basement and a roomy flat on two floors for his own use. Also included in the plans were three small flats to rent out – one of which was regularly leased out to other commercial enterprises.

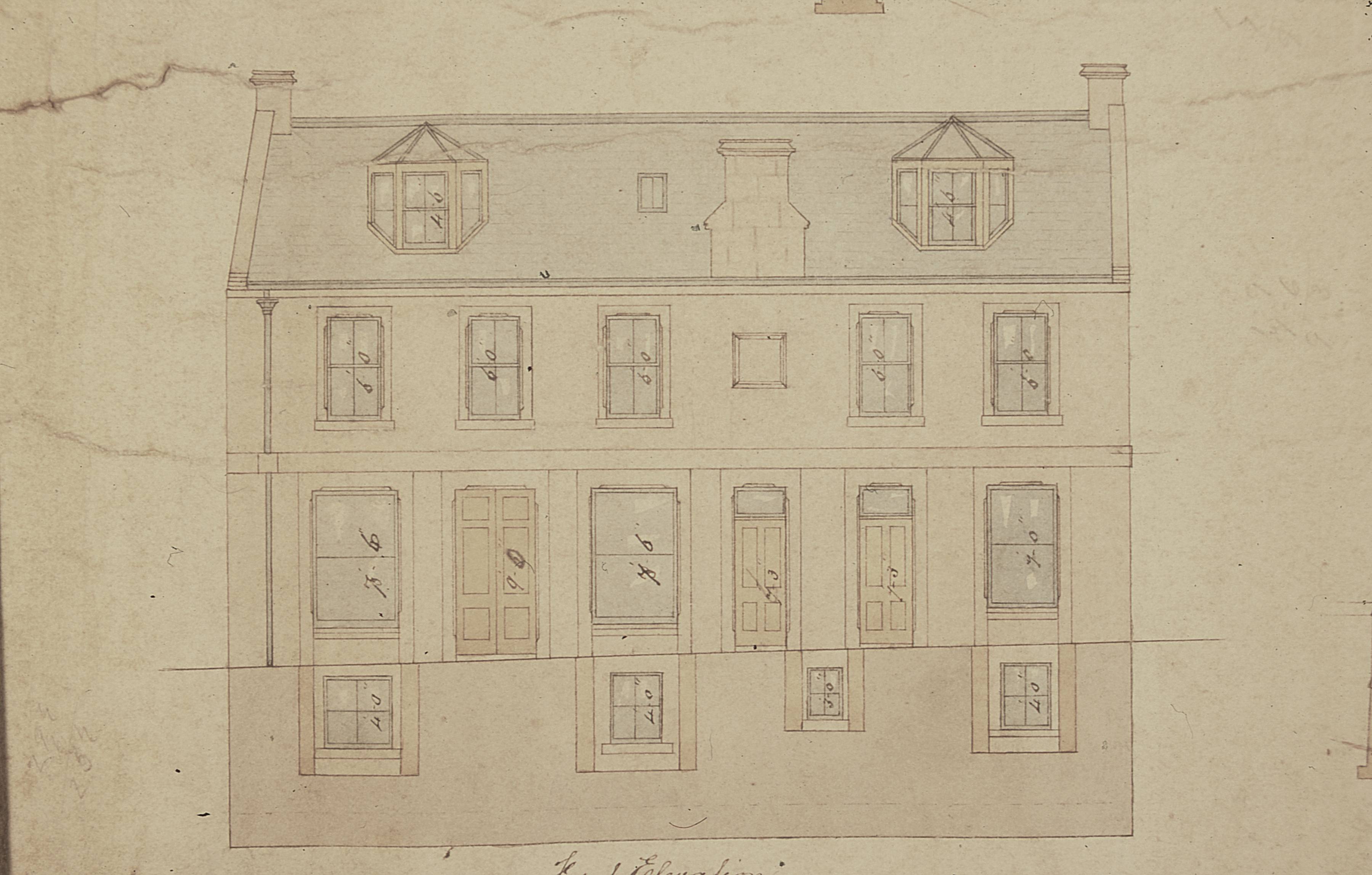

The surviving plan and specification (above) illustrate the level of detail which went into the planning and execution of such an endeavour. From the amount of paint to be used on the door and framings to the dimensions and materials for the windows, the shop was meticulously planned to suit both a commercial and private abode.

Surviving near a century as ‘Whitie Ironmonger and Bootmakers’ (but in truth providing many services) it fell under various management teams including Fred McEwan in 1908, who recalls the arrival of a famous face during his time running the shop:

‘I’ll tell you one anecdote: Lord Roseberry (the ex-Prime Minister) arrived at the shop one day. Sam Perks (he was more than a coachman – a superior coachman) sat in the back. Lord Roseberry held the reins. Sam Perks helped him off and he came in the shop.

‘Young man, I don’t suppose you’ll have what I want.’

‘Excuse me, my lord. I can’t answer that until I know what you want.’

‘A dog dandy.’ ( a dog comb)

‘Bone or aluminium, my lord?’

‘Which do you recommend?’

‘It’s not for me to say, my lord. But the aluminium one will last longer.’

‘Young man, this is a country shop but I’ve had better attention and better supply and cheaper than in London.’

Fred McEwan further recalls further memories and practicalites of his life at the shop. For example, he was dismayed at taking over the enterprise to find that, in fact, very little ironmongering had been taking place at all, but rather, the premise was filled to bursting with ‘boots, shoes, felt slippers, out-of fashion ladies shoes and workmen’s boots’ – a throwback to the shoemaking heritage of the Whitie family. McEwan did, however, have a keen eye in exploiting the local market, he recalls:

‘I could sell six dozen hes to the Irish hoers – some like 6″ blades, some 7″ blades. I always kept plenty of shovels in stock both diamond pointed and square-mouther). The miners had to buy their own. Mr Gibb (the shop owner) supplied all the grates and ranges for the colliery house.’

Sadly, the enterprise eventually closed in 1979 when James Whitie’s grandson David Gibb passed away. What had become a living history of the village also passed on with it.